Seattle-Tacoma Int’l Welcomes the World via New International Arrivals Facility

Seattle-Tacoma International (SEA) recently passed a significant mile marker in its ongoing quest to earn top marks from passengers. Earlier this year, the airport gained a fourth star in its Skytrax rating, and Managing Director Lance Lyttle is confident that a new International Arrivals Facility will help SEA earn a perfect five-star rating and achieve other key customer satisfaction goals.

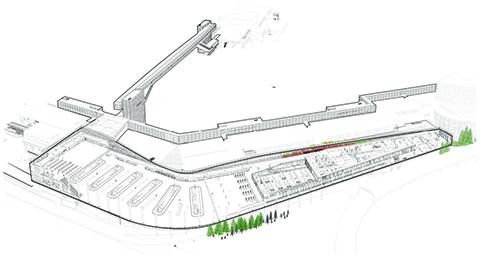

The facility, slated to fully open May 10, has three primary elements: an international corridor, a grand hall and an elevated pedestrian walkway. All were designed to provide a high level of service in a memorable, iconic way. The new facility has four times more space for Customs/Immigration processing, a larger baggage claim area with additional carousels, and improved passenger amenities, including private stations for nursing mothers, additional restrooms and pet relief areas.

The facility, slated to fully open May 10, has three primary elements: an international corridor, a grand hall and an elevated pedestrian walkway. All were designed to provide a high level of service in a memorable, iconic way. The new facility has four times more space for Customs/Immigration processing, a larger baggage claim area with additional carousels, and improved passenger amenities, including private stations for nursing mothers, additional restrooms and pet relief areas.

Lyttle explains that SEA’s previous facility was undersized and its service level was far below what international passengers expect upon arrival. The building was designed to accommodate 1,200 passengers per hour, but was recently processing more than 2,000 passengers per hour at peak travel times. That meant inbound international flights often waited on the tarmac for a gate; and after deplaning, passengers had to wait in corridors because the Customs and Border Protection area was not large enough to process them in an efficient manner. Additionally, the baggage claim area was undersized, which caused more waiting.

|

Project: International Arrivals Facility Location: Seattle-Tacoma Int’l Airport Site: East side of Concourse A Size: 450,000 sq. ft. Cost: $986 million Timeline: 2017-April 2022 Soft Opening: April 19, 2022 Full Opening: May 10, 2022 Facility Features: 8 new swing gates (increasing int’l gates from 12 to 20); larger Customs area & new technology for faster passport checks; pedestrian walkway over taxi lane; 7 larger bag claim carousels; amenities such as nursing rooms, pet relief areas & more restrooms throughout the facility Design/Builder: Clark Construction Architect: Partnership of SOM & Miller Hull Mechanical/Electrical/Plumbing Engineer: ARUP Structural Engineer: KPFF Civil Engineer: MKA Construction Manager: Parsons Pedestrian Walkway Designer: Schlaich Bergerman Partners Passenger Loading Bridge: AERO Bridgeworks Inc. Mechanical/Plumbing Installation: Apollo Mechanical Baggage Handling Systems: Diversified Conveyors Walkway Structural Consultant: SBP Walkway Steel Assembly: The Erection Co. Walkway Mover: Mammoet Walkway Deep Foundations: Condon-Johnson Walkway Fireproofing: American Fireproofing ORAT Software: Citiri Key Benefits: More predictable/less stressful arrival for int’l passengers; more gate options for int’l traffic; higher throughput for Customs processing (2,600 passengers/hr. vs. previous design for 1,200/hr.); minimum passenger connection time reduced from 90 to 75 minutes, and greatly enhanced welcoming views to the region. |

Charles Goedken, SEA’s Operational Readiness and Transition senior manager, notes that airport leaders projected the need for an upgraded international arrivals facility as far back as 2013. Discussions with airlines and the Port of Seattle Commission led to approval of a 450,000-square-foot International Arrivals Facility; and groundbreaking occurred in August 2017.

Crews began by relocating a parking lot for cruise ship buses that was located where the main international arrivals facility building would be constructed. Lyttle notes that aside from that enabling work, the $986 million effort was a “relatively greenfield” project, and much of the construction was completed without impacting airfield operations.

Janet Sheerer, landside project manager for the Port of Seattle, says that planners and designers rose to the challenge of working with a relatively small footprint. “They had to figure out how to make use of gates at the S Concourse and A Concourse in order to get people to what was, in essence, the public side of our terminal,” she explains.

Their solution: the International Corridor, a secure and window-lined walkway that separates international and domestic arrivals on the A Concourse.

International passengers arriving at A gates are treated to a view of the airfield and Olympic Mountains as they proceed through the corridor to the Customs area for processing. Moreover, the project design upgraded eight of the concourse’s existing gates to swing gates, which can handle wide-body international aircraft or domestic aircraft. This brings SEA’s overall capacity of international-capable gates from 12 to 20 gates.

Project designers added four pods to the A Concourse to keep international and domestic passengers separate. “The pods house the new swing gate system and gate doors that control the flow of arriving passengers to the proper destination,” explains Sara Mitchell, resident engineer at Port of Seattle. “Domestic passengers are routed to A Concourse, and international passengers one level up to the International Corridor.”

Phasing was important during construction on the A Concourse because no more than two gates could be out of service at one time, Mitchell adds. This required careful coordination with stakeholders and ultimately minimized operational impact to the airlines.

“We had such a constrained site that we had to play this Tetris game to fit in Customs and Border Protection and meet all of their requirements,” Sheerer says. Despite the challenges, she describes the partnership between the Port and CBP as “incredible” throughout design and construction. “It’s a really amazing facility that’s going to attract passengers and also completely change what it means to work as a CBP person at SeaTac,” Sheerer remarks.

Over vs. Under

When designing the new International Arrivals Facility, one of the big decisions was how to get people from the S Concourse to the new facility—underground or overhead. Ultimately, the project team and airport officials opted for an overhead bridge that provides spectacular views of nearby mountain ranges. “It was not only the better option in terms of customer experience and satisfaction, it was also the cheaper option,” says Lyttle.

Creating the walkway over a taxi lane also minimized operational impact, adds Mitchell. During planning, a study showed that the affected taxi lane would only need to be closed for seven days to accommodate the addition of the walkway. While it ended up taking 11 days, it’s nothing compared to the closure a tunnel would have required, notes Stephen St. Louis, project manager for airside work at Port of Seattle. “That would have crippled our operation for several months.”

Creating the walkway over a taxi lane also minimized operational impact, adds Mitchell. During planning, a study showed that the affected taxi lane would only need to be closed for seven days to accommodate the addition of the walkway. While it ended up taking 11 days, it’s nothing compared to the closure a tunnel would have required, notes Stephen St. Louis, project manager for airside work at Port of Seattle. “That would have crippled our operation for several months.”

The pedestrian walkway connects SEA’s S Concourse to its new International Arrivals Facility in a stunning way. At 85 feet high and 780 feet long, the bridge is the longest over an active taxi lane anywhere in the world, Lyttle reports. “The views as you go across the bridge are spectacular,” he adds. “It’s a totally different type of experience—not only in terms of efficiency, but also aesthetics.”

Looking south, passengers see Mount Rainier; and the Olympic Mountains are visible to the west. The northern view from the bridge features the Seattle skyline, and taxiing aircraft can be seen underneath. “The bridge is phenomenal,” Goedken remarks.

“I think we might experience some of our wait times going up because some passengers will stay up in the pedestrian walkway and marvel at the nearly 360-degree view as they cross over the bridge,” he quips.

The center span of the pedestrian walkway was assembled at SEA’s North Airfield cargo hardstands. The two ends were constructed in-place—one on the S Concourse and the other on the A Concourse. Seven different steel fabricators were used to build all of the walkway components. Lyttle notes that building the bridge safely and securely required continuous coordination with the Operations team. At one point during the project, airplanes were operating in a cul-de-sac-type situation. “But we worked closely with Operations, airlines and project teams to minimize the impact,” he reports.

The center span was slowly carried down the runway one night in January 2020 by four self-propelled modular transporters. Before crews lifted it into place, they performed several hours of site checks to ensure that the pre-fabricated structure lined up with the existing V piers. Once complete, four strand jacks lifted the center span into place. Connection points were welded and bolted into place, completing the entire span of the bridge. The structural steel used to create the walkway weighs 3,000 tons.

Processing Passengers

The new international arrivals facility is designed to accommodate 2,600 passengers per hour, a tremendous increase compared to the previous facility’s capacity. Passengers arriving at the S Concourse deplane and cross the aerial walkway; those arriving from the A Concourse travel through the window-lined, secure International Corridor. Both streams of travelers arrive in the Grand Hall, which features floor-to-ceiling windows that flood the space with natural light from the local environment and provide views of Mount Rainier. From here, passengers retrieve their bags (the new facility has twice as many bag belts as the old facility) and move through Customs processing.

The flow is a new process from Customs and Border Protection called Bags First. Typically, passengers arriving on international flights go to passport control, retrieve their bags and then begin the Customs process. In SEA’s new facility, passengers will deplane, retrieve their bags and then go through a single Immigration/Customs process. “It’s a major change,” says Lyttle. “It’s far more efficient, and I think our customers are going to love this process much better.”

When the former Federal Inspection Station was still operating, the minimum connect time for international travelers was 90 minutes, which Lyttle says was “unacceptable from a passenger perspective.” The goal at the new facility is 75 minutes from the time of arrival, through Customs and Immigration and to a connecting flight.

SEA is the first large hub to use the Bags First processing from Customs and Border Protection. Having passengers pick up their bags before reaching the CBP Passport Control area is part of the airport’s overall effort to expedite the connecting process. At first, Automated Passport Control kiosks were to be used on the upper mezzanine level. Without them, the design team added the flexibility of another escalator to the baggage level to provide more throughput to the lower level. “Initially, we were going to have all passengers use the Automated Passport Control kiosks, then filter down to pick up bags, go to Passport Control and then out,” Goedken recalls. “However, CBP updated their design to do facial recognition and Bags First. That was a big challenge, but the partnership with them has been very good.”

SEA is the first large hub to use the Bags First processing from Customs and Border Protection. Having passengers pick up their bags before reaching the CBP Passport Control area is part of the airport’s overall effort to expedite the connecting process. At first, Automated Passport Control kiosks were to be used on the upper mezzanine level. Without them, the design team added the flexibility of another escalator to the baggage level to provide more throughput to the lower level. “Initially, we were going to have all passengers use the Automated Passport Control kiosks, then filter down to pick up bags, go to Passport Control and then out,” Goedken recalls. “However, CBP updated their design to do facial recognition and Bags First. That was a big challenge, but the partnership with them has been very good.”

Audio announcements and signage were added to inform travelers about the change and guide them through the new process.

That Pacific Northwest Feeling

In addition to increasing throughput, SEA focused on creating a facility that was intuitive for passengers to move through. It was also important for the design to reflect the look and feel of the Pacific Northwest, notes Lyttle.

In the Grand Hall, the tilt of the roof is designed to resemble an airplane landing. It also brings in natural light and maximizes views to guide travelers through the facility.

Colors, architectural elements, artwork and materials were selected to welcome travelers and create a sense of place. Floor-to-ceiling windows, for instance, provide views of sunrises and mountains, and allow natural light to stream into the Grand Hall. Wood accents bring warmth and nature into the space. Designers chose materials in sea and sky blues, as well as greens and organic textures of the mountains and forests. More than 100,000 square feet of terrazzo floor sourced from local stone form a rock pattern that evokes the colors and textures of a rocky Pacific Northwest beach.

The new Grand Hall, which was added adjacent to the A Concourse, needed to be separated from the existing structure for seismic reasons. In the event of an earthquake, both structures need space to move independently. To solve this challenge and add visual appeal, architects filled the area between the buildings with Pacific Northwest trees, ferns, basalt and other natural elements found in the forest. “It really was an opportunity that came from a problem,” Sheerer reflects. “People are going to feel that sense of place—a little chunk of forest as you’re entering the country.”

The new Grand Hall, which was added adjacent to the A Concourse, needed to be separated from the existing structure for seismic reasons. In the event of an earthquake, both structures need space to move independently. To solve this challenge and add visual appeal, architects filled the area between the buildings with Pacific Northwest trees, ferns, basalt and other natural elements found in the forest. “It really was an opportunity that came from a problem,” Sheerer reflects. “People are going to feel that sense of place—a little chunk of forest as you’re entering the country.”

Artwork throughout the new facility is something “spectacular for passengers to see,” Goedken adds. Chalchiutlicue, a five-piece sculpture by artist Marela Zacarías that hangs over the bag claim carousels, was inspired by the colors of the waterways and sunsets in the San Juan Islands, north of Seattle. Another installation, Magnetic Anomaly, includes three kinetic artworks by Ned Kahn. The spinning, suspended metallic mobiles were inspired by the wind and ever-changing Pacific Northwest weather. Other works by six Native American artists, including glass artist Preston Singletary and the interdisciplinary artist Marie Watt, will also be on permanent display in the new facility.

To fulfill the Port’s mission of environmental stewardship and sustainability, the new International Arrivals Facility is designed to achieve LEED Silver Version 4 certification. Standout elements include:

- low-flow restroom fixtures to reduce indoor water use

- energy-saving features like LED lighting, energy-efficient escalator motors and variable speed motors on baggage handling devices

- daylighting to connect travelers to the outdoors, reinforce circadian rhythms and reduce energy consumption

- conscientious construction, with 7,163 tons of contaminated soil and 62,405 gallons of impacted stormwater removed from the project site

- sourcing many materials from within 100 miles; use of low-emitting adhesives, materials and coatings

- diverting most of the construction waste from landfills

Prepare for Takeoff

Officials at SEA place just as much emphasis on the operational readiness of a new facility as its design and construction. The International Arrivals Facility had to be able to process 2,600 passengers per hour, and Lyttle and other airport leaders expected the passenger experience to be optimal on opening day.

Ensuring that facilities open successfully and operate the way they should is why SEA has its own in-house operational readiness and transition (ORAT) team. “It’s a permanent feature of our airport now,” says Lyttle. “We’re not just starting it up and demobilizing it on each project.”

The airport’s ORAT team leads the activation and opening of new facilities in close collaboration with federal agency and airline partners. Prior to opening the International Arrivals Facility, SEA employees, tenants and frontline staff took familiarization and training tours that covered airline and ground handler operations, passenger processing, carousels and baggage handling systems, new operating procedures, waste management, restrooms and other amenities. They also participated in security and emergency response drills.

“As you’re planning and building a new facility, you need to talk to stakeholders—find out who is using the facility, who is around the facility and who is going to occupy it,” relates Goedken. This helps ensure that Operations teams are familiar with their new workplaces. Operational trials allow the ORAT team to verify that the facility and its systems meet stakeholder and passenger needs.

“Some people think ORAT comes at the tail end of a project,” Lyttle relates. “For us, it starts in planning.”

With additional projects slated for years to come, having an in-house ORAT team benefits all of SEA, Goedken adds. It manages organizational and project knowledge from design through opening, ensuring that new facilities meet operational needs and people know how to operate within them, he explains.

About 2,000 employees were trained about the ins and outs of the new facility prior to opening day. “We give them a very detailed familiarization and induction training tour,” says Goedken. Preparatory sessions included exploring all exits, validating that all equipment works as it should and reviewing standard operating procedures.

With the help of hundreds of volunteers, SEA conducted a passenger flow simulation to evaluate passenger journey elements such as elevators and escalators, wayfinding and signage, baggage claim, amenities, inspection and re-check.

The airport took a measured approach to opening the new International Arrivals Facility, beginning with a soft opening that ran a few early morning flights through the facility beginning the week of April 19. “That soft opening is the benchmark,” Goedken relates. That phase lasted roughly three weeks and allowed the team to “hammer out any further issues.” The complete cutover then occurred overnight.

Challenges Yield Lessons

For Goedken, this has been SEA’s most complex project because it spans landside, terminal and airfield areas, and it involves more than 20 airlines and five federal agencies. “From an ORAT perspective, you can never start planning early enough,” he advises. “And you always want to make sure that you have the right people in the room and that you share information, because that affords the best opportunity for success.”

Lyttle notes that the project encountered unexpected challenges that delayed the schedule. “But at the end of the day, when we look at the type of service we’re going to be providing to the passengers and airlines using this facility, it was worth the wait,” he remarks.

One early challenge was the discovery of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in the soil at the project site. The toxic compounds were from an old airline hangar torn down long ago, and crews needed extra time to properly clean the area.

Space was another challenge. The small building footprint translated into a cramped workspace for contractors. “The physical constraints were one of the biggest challenges for the contractor trying to build at an active airport,” says St. Louis. “Being cognizant of that as an owner is really important.”

Like at other airports, the pandemic provided opportunities to accelerate some aspects of the project, including the chance to shut down additional gates or taxi lanes for a longer period of time to facilitate construction. “That was kind of a silver lining in the cloud, if you could find any for the pandemic,” says Lyttle.

After the center span for the pedestrian walkway was erected and the taxi lane reopened to aircraft, there was still an enormous amount of work needed to finish the bridge. In order to complete that work and not impact operations, contractors worked between 10 p.m. and 5 a.m., when the taxi lane was closed. “Then COVID happened, and we were able to shut it down for about 45 days straight to finish up the work,” recalls St. Louis. “Had it not been for COVID, we would have continued with nightly taxi lane closures for several months to finish all the work that needed to happen.”

Lyttle notes that COVID-19 also provided another unexpected upside. “We were able to use projects such as the International Arrivals Facility to continue to provide jobs in the midst of a pandemic,” he explains. “This project continued the economic activity for this region and thousands of people who depend on it.”

The airport’s ability to keep the project moving forward was not lost on project partners like Phil Ellsworth, director of construction at Parsons. “It’s been exciting and an honor helping an airport like Seattle continue to grow—especially with COVID in the middle of this project,” he comments. “Seattle kept it rolling.”

The airport’s ability to keep the project moving forward was not lost on project partners like Phil Ellsworth, director of construction at Parsons. “It’s been exciting and an honor helping an airport like Seattle continue to grow—especially with COVID in the middle of this project,” he comments. “Seattle kept it rolling.”

Regarding the turnover that many long-term projects experience, Goedken advises airport operators and their stakeholders to have a succession plan. This helps minimize the loss of team cohesion and tribal knowledge when and if turnover occurs, he explains.

Something New for SEA

Using the progressive design-build method for the International Arrivals Center was a learning experience for all involved, because it was the first time SEA took that strategy. In retrospect, Lyttle says it is important for the entire organization, consultants and contractors to be prepared to function differently than they would under a traditional design-build or design-bid-build delivery method. “At the time the decision was made, we were probably not culturally ready, so we had to get acclimated as the project went along,” he reflects.

Lyttle also suggests speaking with other airports that have experience with the delivery method to better understand the pros and cons. “I think it would be extremely helpful for the permit leaders and the key people within the project to speak with those folks and understand the ins and outs of this type of delivery method,” he states.

Sheerer notes that some lessons learned led to interesting solutions. For example, the team was able to make changes to the baggage system fairly seamlessly that, under another delivery method, would have likely been much more involved.

“We jumped in big for the very first one,” she says. “I wholeheartedly applaud our leaders for taking that leap—not only investing that kind of money, but also the trust in us and the designer and contractor to do this new delivery method.”

Mitchell adds that from a project management perspective, the early collaboration that occurred under the progressive design-build delivery method was critical.

Ultimately, Sheerer plans to apply the collaborative model to SEA’s next projects. “It worked really well for us,” she concludes, noting that the International Arrivals Facility was the most collaborative project she has ever experienced.

FREE Whitepaper

PAVIX: Proven Winner for All Airport Concrete Infrastructure

International Chem-Crete Corporation (ICC) manufactures and sells PAVIX, a unique line of crystalline waterproofing products that penetrate into the surface of cured concrete to fill and seal pores and capillary voids, creating a long lasting protective zone within the concrete substrate.

Once concrete is treated, water is prevented from penetrating through this protective zone and causing associated damage, such as freeze-thaw cracking, reinforcing steel corrosion, chloride ion penetration, and ASR related cracking.

This white paper discusses how the PAVIX CCC100 technology works and its applications.

facts&figures

facts&figures